Weath of Nubia Target of Egyptian Agression:

Sophia Flint

Nubia was an area gifted with raw natural resources as well as prolific trade hubs for goods from as far as Sub-Saharan Africa. Through trade and naturally produced commodities, Nubia provided Egypt with luxury goods such as ebony, acacia wood, exotic animal skin, semi-precious stones, ivory, copper and gold (Roy, 271.) Egyptian pharaohs realized that the economic gains that could be had from requisition of the Nubian resources and trade routes, made dominion over the territory an attractive prospect. It was the wealth of Nubia that encouraged Egypt’s continued efforts to seize it. Pharaohs made Nubia a priority from the Early Dynastic through the Middle Kingdom periods by a series of dominations, withdrawals and re-conquest of the area.

In the Paleolithic and Neolithic eras, Egypt and Nubia were not separate nations, but similar nomadic people that existed along the banks of the Nile (Shaw, 18.) As each developed their own separate cultural identities, Nubia established itself as a great source of intellectual, technological and commercial value to Egypt. It was from Nubia that the Egyptians gained the first livestock that allowed them to develop their agriculture; it was also from Nubia that the Egyptians learned blade knapping techniques, (Shaw, 18.) There is also archeological evidence of trade with Nubia from ebony found at Naqada II sites (Roy, 270.) This relationship of mutual exchange soured after the Pre-Dynastic Age, when Nubia’s wealth turned them from trade ally into a target for Egyptian aggression.

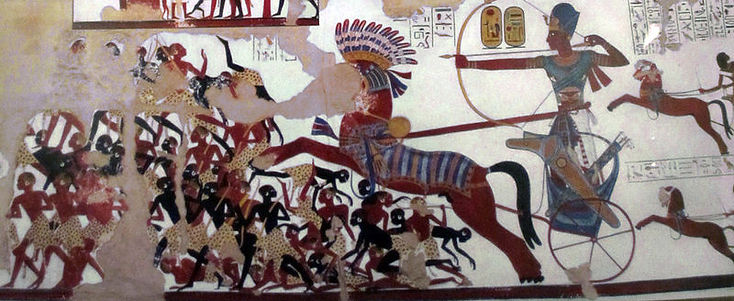

Egypt’s relationship with Nubia during the Old Kingdom was described as a series of “sporadic and uncoordinated raiding and trading” with no desire to have a sustained presence in the region (Adams, 165.) Once Egypt achieved unification in the late Pre Dynastic Era, the Egyptians pharaohs ordered the first military incursions into Lower Nubia (Shaw 61.) Ian Shaw suggests that the Nubians would have been outnumbered and unable to fend off the Egyptian invasions of Dynasty 0 and Dynasty 1. The shallow the floodplains of the Nile River of Nubia did not have the agricultural potential to sustain a large population, and the face of invasion the inhabitants would have been driven out of the area (Shaw 63, 73.)

Major Egyptian exploitations of Nubia’s assets were made by Sneferu during Dynasty 4 where troops were sent into Nubia in order to expand Egypt’s economic prospects. Egypt need raw materials for major building projects that occurred during the Old Kingdom. Archeological evidence from The Palermo Stone records that among the spoils of war from Sneferu’s campaign was 20,000 cattle, 7,000 captives, as well as natural resources like wood (Shaw 97.)

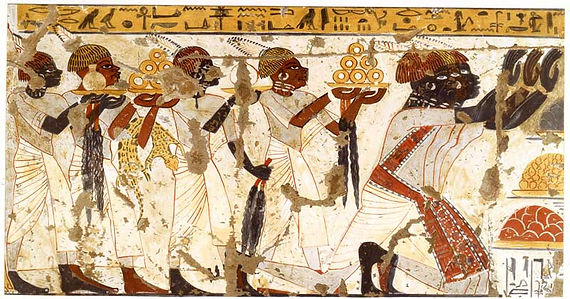

The tomb of Harkhuf, the governor of Aswan under the pharaohs, Merenre and Pepi II, described four expeditions the pharaohs ordered into Nubia during the 6th Dynasty (Roy, 272.) Each time he returned from Nubia with tribute for king from the people of the region. Harkhuf’s third expedition he returned with a dancing pygmy and on the fourth expedition he returned with an exhaustive list of goods including, 200 donkeys, honey, sacred oils, panther and leopard skin, elephant tusk and throwing sticks (Roy, 275.) Foreign commerce like this would have only been attractive for the king and his court, therefore any directives to invade Nubia would have been a “royal enterprise” (Adams, 167.) Egypt was pushed out of Nubia due to political instability at the end of the Old Kingdom period, however the military inroads would continued into the Middle Kingdom with increasing severity.

Nubia was lost and recaptured many times during the Old and Middle Kingdoms. However, it was so vital to the wealth and economy of Egypt that most Egyptian rulers achieved reoccupation of Lower Nubia during their reign. Recapture of Nubia was made by notably kings like Mentuhotep II, after the second unification of Egypt and again during the reign of Amenemhat (Shaw 141, 148.) The seizure of Nubia under Senusret III had been particularly brutal, where soldiers murdered many Nubians, burned their homes, poisoned wells and enacted harsh travel sanctions. All this was an effort meant to depopulate the area to make future conquest easy as well as flex Egyptian hegemony (Shaw, 154.) Middle Kingdom incursions into Nubia were more invasive, the Nubians were forced to pay tribute and lived under the rule of an Egyptian viceroy as a colonial annex of Egypt (Adams, 165.) The Egyptians of the Old Kingdom wanted to control the trade through Nubia and archeological evidence from this period shows Egyptian border check points, forts and trade centers around Abydos. These structures established both Egyptian influence and border control along the trade routes of northern Nubia (Shaw 73.)

By the Middle Kingdom the Ancient Egyptians had exhausted many of the gold and mineral reserves in their own territory and they were soon looking for new sources. Gold was important to the Pharaohs of Egypt, because they used it to display their vast wealth, decorate their increasingly ornate tombs and because they believed the material to be the skin of the Gods (Roy, 288; Adams 168.) The gold ore was mined from stores found in the mountain regions adjacent to the Nile River. Lower Nubia then became a target for their mineral ore and gem quarries. The quarries provided diorite, granite, amethyst, and copper used in both art, jewelry, temples and tombs (Shaw 194.) However, Egypt became politically unstable and had to retreat out of Nubia once more. Over the course of history Egypt would recapture it several more times, eventually, they were driven out and in Dynasty 25 when Nubia was able to conquer Egypt (Shaw, 364.)

Ancient Egypt’s relationship with Nubia was important to its cultural and economic development especially prolific during the early Dynastic periods. Egypt craved opulence and with each incursion into Nubia they gained great wealth. The region’s assets as a trade port and rich natural resources made it an attractive target to Egypt who repeatedly vanquished it in order to monopolize trade resources and exploit the wealth of Nubia to the commonwealth of Egypt.

Works Cited:

Adams, William Yewdale. Nubia, Corridor to Africa: Princeton, N. J.: Princeton University Press, 1977. Accessed November 1, 2014. ProQuest ebrary.

Roy, Jane. Culture and History of the Ancient Near East, Volume 47 : Politics of Trade : Egypt and Lower Nubia in the 4th Millennium BC. Leiden, NLD: Brill Academic Publishers. 2011. Accessed November 2, 2014. ProQuest ebrary.

Shaw, Ian. The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000.