The New Kingdom brought forth some of the most eminent rulers of Ancient Egyptian History. However, rule was not exclusive to men. The accomplishments of Hatshepsut helped the sustainability of Ancient Egypt because of her ability to invoke right to rule by royal blood ties, aptitude for leadership and public works programs that maintained peace and the economic and political prosperity of Upper and Lower Egypt until such time that it was appropriate for her co-emperor, Thutmose III to succeed her. There is no evidence to support her ascension as a personal power grab or coup, but a political maneuver aimed at dynastic preservation.

Hatshepsut was only the third female pharaoh and the first to attain a sustained rule with the full power of Upper and Lower Egypt. She had been born into the royal line as the daughter of the preceding pharaoh, Thutmose I. She came to power after the death of Thutmose II to whom she was both primary wife and sister. Hatshepsut’s father’s reign had been well remembered as a highpoint in Egyptian imperial power and prosperity. Thutmose I was a popular leader among the Egyptians who was rewound for his of military exploits in Nubia.[1] Hatshepsut was able to invoke support through her father’s accomplishments and accolades that rather than through her time as Thutmose II’s Queen who was considered an ineffectual king, unable to capture the glory of his father.

[1] (Wilson 2006, 1)

[2] (Robins 1993, 46)

[3] (Watterson 1991, 139)

[4] (Wilson 2006, 2)

[5] (J. Tyldesley 2001, 2)

[6] (Wilson 2006, 3)

[7] (Myśliwiec 1985, 2)

[8] (Robins 1993, 52)

[9] (Myśliwiec 1985, 36)

[10] (Lichtheim 2006, 199)

[11] (Tyldesley, Hatchepsut : The Female Pharaoh. London 1996, 210)

[12] (Tyldesley, Hatchepsut : The Female Pharaoh. London 1996, 252-253)

[13] (Robins 1993, 51)

[14] (Watterson 1991, 140)

[15] (Wilson 2006, 2)

[16] (Myśliwiec 1985, 9-11)

[17] (Watterson 1991, 140)

[18] (Robins 1993, 152) (Watterson 1991, 139)

[19] (Wilson 2006, 3)

[20] (Watterson 1991, 139)

[21] (Wilson 2006, 3)

[22] (Myśliwiec 1985, 6)

[23] (Tyldesley, Hatchepsut : The Female Pharaoh. London 1996, 125)

[24] (Wilson 2006, 2)

[25] (Watterson 1991, 140)

Thutmose II had died young, and the only male successor to his throne was Thutmose III, the infant son of his minor wife, Aset.[2] Situation like these left dynasties in politically precarious positions.

The death of a king was always a dangerous prospect, power in Ancient Egypt was seen to have been bestowed divinely and the pharaohs were seen as living gods. Their right to rule was imbued by the god Horus to uphold their ideals of “Maat.” For rulers that died without suitable heirs like young children that were unable to assume responsibility as pharaoh, it would often fall to capable wives and daughters to assume control. Without someone to maintain control of a central government, curb any potential rebellions and hold onto the unity of Upper and Lower Egypt, the civilization would soon be subverted by usurpers and political rivals which would often lead to civil war or invasion from outside. It was important then that Hatshepsut not only had the proper pedigree, but could maintain rule in their own rights.

A practice that persisted in the royal genealogies of the Ancient Egyptian, are the instances of incest. Inbreeding between brother and sister was both cultural practice among the royals without taboo and a political tactic meant to keep power contained within a single familial dynasty. With Hatshepsut, marriage to her half-brother Thutmose II may have helped her assent to power since she held both a blood and marital claim to the throne.[3] Despite any political justification of her right to the throne, her primary motive in assuming the role of pharaoh appeared to be political and aimed at the preservation of the Thutmosid Dynasty.

After the death of her husband, Hatshepsut assumed the responsibilities of affairs of state to conserve the dynasty as Thutmose III’s regent since the infant was too young to rule. This conservatory role would have been a conventional position for a woman of Hatshepsut status and the standard practice for maintaining rule while the true heir came of age. Where Hatshepsut broke with tradition is the further step she took to become the pharaoh herself with Thutmose III as co-ruler of Egypt. The decisive claim that Hatshepsut made seven years in her regency suggest this was not a move motivated by personal ambition, but a likely a bold response to a political threat that had emerged from a competing branch of the royal family or external political entity while Thutmose III was still a child.[4] There is no evidence that indicated that this was intended to depose the infant or to separate him from his birthright. In fact, Thutmose III was considered co-ruler of Egypt for the duration of Hatshepsut’s reign in a similar fashion that dynastic power was shared between father and son. This interpretation is further supported by Hatshepsut’s treatment of Thutmose III during her reign. She saw to it that he was educated in a manner befitting his future to the throne. He was educated in literature and military affairs and had joined the army at adolescence and led a campaign in the Levant. By adulthood, Thutmose III had risen to the rank of Commander in Chief in the Egyptian army, which would indicate that Hatshepsut had no reservations of him commanding an army capable of taking action against her.[5]

The destruction of Hatshepsut’s monuments, had been postulated to be out of Thutmose III’s personal animosity towards a usurper and begun shortly after Hatshepsut’s death. However, evidence now shows that this was ordered nearly 20 years after he assumed power, toward the end of his own long reign when Thutmose III’s would have been considering the ascension of his own son, Amenhotep II.[6] The fact that it happened so late in Thutmose III’s reign suggested that he was responding to a demand that made it necessary for him to augment history in order to protect the legitimacy of his own son. Some historian suggest this was an overture to tensions that led to the “religious revolution” and destruction of iconography and during Amarna Period[7]. However, more likely it was a political action to remove anything that set a precedent for a powerful woman to insert herself into the dynastic flow.[8] This is evident because while his effort to remove traces of Hatshepsut’s reign were concentrated it was not thorough, any many images were left at the complex at Deir el-Bahri.[9]

The argument that the destruction of her monuments was in retribution for keeping him away from the throne or anything aside from political maneuvering is shortsighted. Thutmose III would have been in his early 20’s when he came to full power after Hatshepsut’s death. This was not much older than when most other pharaohs came to power, and completely age appropriate as illustrated in a passage from the Insinger Papyrus:

He <man> spends ten <years> as a child before he understands death and life.

He spends another ten <years> acquiring the work of instruction by which he will be able to live.

He spends another ten years gaining and earning possessions by which to live.

He spends another ten years up to old age, when his heart becomes his counselor.

There remain sixty years of the whole life, which Thoth has assigned to the man of god. [10]

Although there is evidence of children coming to assume the full power of a pharaoh it often happened because there was no other suitable option, where with Hatshepsut and Thutmose III she gave him the luxury to reach maturity and inherit a stable and prosperous country. The last years of the co-regency gives further evidence that the smoothtransition of power between she and her stepson was purposeful and imminent as the artist depictions of the kings changed to reflect the two as equals and not Hatshepsut as the dominant figure as in years previous.[11] The stela of Nakht from Sinai that is dated two years before the death of Hatshepsut, and shows her and Thutmose III as equal figures jointly making offerings to the gods.[12]

This evidence would indicate that Hatshepsut acted to save the throne for her stepson and avoid destabilization of Egypt. Since Hatshepsut’s primary motivation was dynastic preservation she had nothing to gain by unseating someone who was stepson, heir and nephew; and had she wanted to eliminate him as a political rival it is hard to believe that a woman who seized control of Egypt could not find opportunities over 20 years of reign. For this reason her power grab was for the sustainability of her Dynasty meant for the benefit of Thutmose III. There is no evidence of any animosity between them and the paradigm of the evil step-mother has little bearing in Ancient Egypt. It is far more likely that Hatshepsut’s successful reign set a dangerous model that needed to be suppressed because her right of assentation was justifiable and effective.

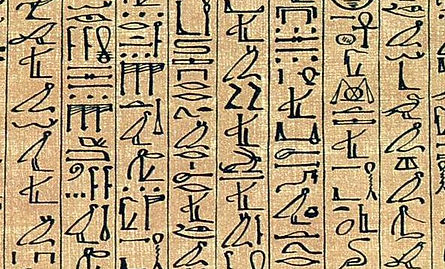

Hatshepsut ascension was unconventional, although it was a politically legitimate claim. Gender equality was not a predominant convention in Ancient Egypt and her sex would have always been an issue. It is in this spirt that she began the campaign to portray herself with the masculine dimorphic features, because a woman wielding such enormous power was unheard of.[13] The art at the time of her becoming pharaoh shifted from feminine and demure to masculine and of central prominence dressed in the pharaoh’s robes, false beard and double crown of Upper and Lower Egypt.[14] At the same time she adopted new names and titles for herself such as “Daughter of Re” and Maatkare, to call attention to the fact she was now in charge of the ancient Egyptian expression for order and justice, “Maat,” which was directed from gods to pharaohs.[15] To illustrate the validity of her divine connection to the pantheon, Hatshepsut decorated her temples with of pictorial propaganda that showed the symbolic ties between her role as pharaoh and the gods’ benediction. One relief shows the goddess Hathor, patron of the capitol at Thebes, licking the hand of the ruler.[16] Another shows Hatshepsut’s own birth depicted as the divine offspring of Amun and Queen Ahmose.[17] Preservation of “Maat” and mediator between the people and the gods was the pharaoh’s prerogative and ensured the future prosperity and stability of Egypt. All this was an effort by Hatshepsut was a political image campaign to assuage any fear that Egypt did not have a legitimate ruler on the throne, something she would validate during her two decade rule over Egypt.

Hatshepsut’s successful transition from regent to pharaoh relied in part on her ability to surround herself with a strong group of loyal and powerful supporters. Again Hatshepsut used her father’s influence and sought to recruit officials that had served her father and placed them into in key positions within her own government. This included her Vizier Ahmose and high ranking temple officials like Hapusoneb who helped solidify her political power by support of her claim to the title of “god’s wife” which gave her the authority over temple rituals.[18] The most influential members of her court was Senenmut, who had begun his career as an educational tutor to Hatshepsut’s daughter with Thutmose II, Neferure. He became her chief minister and would be endowed with over 93 titles[19], several dedicated monuments and a tomb near Hatshepsut’s in the Valley of the Kings.[20] This man would be influential during her reign and as Great Steward of Amun he helped her realize her vast public works project through the Egyptian Empire as well as trade missions to foreign parts. Senenmut was the overseer of works at Deir el-Bahri and placed in charge of all of Karnak’s building and business activities.

Egypt’s political and economic prosperity flourished under Hatshepsut’s reign due in part to her promotion of homegrown public works measures rather than disrupt Egypt with any attempts at military campaigns with expansionist designs. As pharaoh, Hatshepsut undertook ambitious building projects that contributed to employment in Egypt especially in areas around Thebes. Architecture was aimed at the glorification of her reign and of the Thutmosid Dynasty and was an enormous enterprise that involved an army of workers.

She ordered a pair of red, granite obelisks that stood over 10 stories tall erected at the Temple of Amon at Karnak. She also built the temple complex at Djeser-djeseru that served as her funerary cult and was considered one of the greatest architectural achievement of the Ancient World. At this location is the enormous memorial temple at Deir el-Bahri which she adorned this temple with images of herself. Over 100 colossal statues of Hatshepsut as a sphinx lined the terraced courtyards and processional path. The temple’s lower levels featured pools and gardens planted with fragrant trees.[21]

Hatshepsut’s own tomb in the Valley of the Kings was a symbolic palace that included two cult temples dedicated to the Theban gods, Hathor and Anubis; as well as a temple chapels cults dedicated to her father, Thutmose I, whom she had exhumed and reburied in the in the tomb intended to share with him.[22] With this act she invoked the memory of her father as yet another attempt to legitimize her rule. On the tomb of Thutmose I is the following inscription:

…The king of Upper and Lower Egypt, Maatkare, the son of Re, Hatshepsut-Khnemet-Amun! May she live forever! She made it as her monument to her father whom she loved, the Good God, Lord of the Two Lands, Aakheperkare, the son of Re, Thutmosis the justified.[23]

.

The fragmentary records of the achievements of Hatshepsut’s reign can be seen in what remains of stone relief art in and around her temple at Djeser-Djeseru. There are depictions that commemorate raising of the obelisks at Karnack that shows them being towed along the Nile by 27 ships thast were manned by 850 oarsmen.[24]

There are also a series of reliefs marking her trade missions to Punt, postulated to be on the coast of the Red Sea near day Eritrea. The reliefs show the Egyptians loading their boats in Punt with an array of highly prized luxury goods like ebony, ivory, gold, exotic animal skins, oils and incense trees.[25] The importance of the building projects and the import of high end luxury goods is that it indicated the heath of the Egyptian economy under Hatshepsut, which was a core feature of her successful reign.

Gender equally in the Ancient world was far from the social norm. Hatshepsut as a royal woman with wealth and status was able to actively assume control of the political, economic, diplomatic, and military spheres of Ancient Egypt. Hatshepsut underscored of her political legitimacy, by pointing to her royal lineage and invoking the memory of her father and then proving her worth once on the throne. Despite her accomplishments, her position as a female in power would prove to be threatening to any successors and erasing her memory was seen to be important to the continuation of a stable dynasty.

Works Cited

Lichtheim, Miriam. 2006. Ancient Egyptian Literature: Volume III: The Late Period. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Myśliwiec, Karol. 1985. Eighteenth Dynasty Before the Amarna Period. Leiden: E.J. Brill.

Robins, Gay. 1993. Women in Ancient Egypt. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press.

Tyldesley, Joyce. 1996. Hatchepsut : The Female Pharaoh. London. New York: Viking.

Tyldesley, Joyce. 2001. "Hatshepsut and Tuthmosis: a royal feud?" BBC History. Oct 1, 2001. Accessed 11 10, 2014. http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/ancient/egyptians/hatshepsut_01.shtml.

Watterson, Barbara. 1991. Women in Ancient Egypt. New York: St. Martin's Press.

Wilson, Elizabeth B. 2006. "The Queen Who Would Be King." Smithsonian Magazine Vol 37 ( Issue 6): PP 1- 4. Accessed November 10, 2014. http://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/the-queen-who-would-be-king-130328511/.