The world of the Ancient Egyptians existed as a staunch funerary culture. The Ancient Egyptians believed that the journey to the Afterlife required grave goods that were carried with the deceased beyond death. As a result, nobles and the wealthy were entombed with valuable luxury goods such as jewelry made of precious stones and metals like gold, fine cloth, furniture, oils, spices, incense as well as food and wine.[1] The vast riches buried within the tombs were a tempting draw to tomb robbers, however, being caught carried heavy penalties and the guilty were imprisoned, tortured and sentenced to gruesome executions that were designed to deny them access to the Egyptian Afterlife. In the New Kingdom, the lure of treasure was not deterred by temple defense, celestial punishment or judicial penalty and tomb robbery thrived in Ancient Egypt.

Many tombs were difficult to access since they were often sealed once the body had been enshrined.[2] There were many obstacles potential thieves had to navigate in order to reach the goods inside. The tombs were often protected by guards and constructed with hidden burial and treasure chambers, the burial shafts were also sealed with stone slabs that blocked any obvious entrance.[3] Consequently, raiding a New Kingdom tomb required a lot of effort and crew of people. For this reason, the evidence shows that most of the robbers in the New Kingdom were those with working knowledge of the tombs’ construction. Often when thieves were caught the court document shows a conspiracy on various social levels. Accomplices often included the tomb builders, masons, temple scribes as well as the tomb officials themselves. The vast amount of papyri of judicial inquiries would suggest that the temptation to grave rob would overcome most preventive measures. The Papyrus Salt 124, contained a petition from a workman called, Amennakhte that denounces the tomb foreman Paneb as a thief. He states:

And when the burial of all the kings was made, [I reported(??)] Peneb's theft of the things of King Sety Merenptah. The list of them:......storehouses of the king Sety Merenptah, which were found in his possession after the burial......and he took away the covering (?)of his chariot. They cut the hand of......the scribe, though (?) he took it at the burial. )[ ...... the five ...... ] of the doors. And theyfound the four (of them), but he took away the one. It is in his possession.[4]

Along a similar vein, the Amherst Papyrus records the confession of a robber called Amenpanufer and seven other builders.[5] The Abbott Papyrus that is dated to the 20th dynasty, contains an inquiry that implicates the Theban mayor in a conspiracy of tomb robbing.[6] This several examples listed would suggest that theft was rampant in the New Kingdom and would advocate the position that temple defense and criminal punishments did little to stop thieves.

Tomb robbing carried harsh capital as well as celestial punishments. There were often curses inscribed on the tomb walls that spoke of the god’s wrath in the Afterlife that would be enacted should any robbers enter the tomb. An example is an inscription the tomb of Petety in the Cemetery of the Pyramid Builders that reads:

Listen all of you! The priest of Hathor will beat twice any one of you who enters this tomb or does harm to it. The gods will confront him because I am honored by his Lord. The gods will not allow anything to happen to me. Anyone who does anything bad to my tomb, then [the] crocodile, [the] hippopotamus, and the lion will eat him.[7]

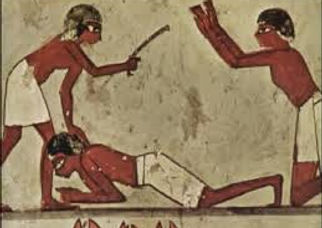

The earthly punishments for those convicted as tomb robbers were extremely harsh and evolved torture, mutilation and death. The evidence on the Amherst Papyrus demonstrates that torture was used to prompt confessions from suspected tomb robbers. The document describes the methods of torture as severe beating on the hands and feet at which the culprit was forced to name any accomplices in the robbery, to reveal what had been done with any stolen goods and to describe how they had accomplished the crime.

A passage from the Amherst Papyrus reads: “TOTAL, people who had been in the pyramid of this god, 8 men. Their examination was effected by beating with sticks, and their feet and hands were twisted. They told the same story.”[8]

A second passage from the same document has a description of the admission. The papyri has the confession from the criminal and explains how the robbers located and broke into the tombs and also a description of the looting of the mummies and objects from tombs:

We collected the gold we found on the noble mummy of this god, together with (that on) his amulets and jewels which were on his neck and (that on) the coffins in which he was resting, [and we] found [the] queen in exactly thesame state. We collected all that we found upon her likewise, and set fire to their coffins. Wetook their furniture which we found with them consisting of articles of gold, silver, and bronze, and divided them amongst ourselves.[9]

Another method of torture that was used on thieves was mutilation of the body, often the criminal would have their nose, ears and hands cut off. David Lordon describes a particular judicial papyrus that list the punishment of the tomb robbera. The papyrus says, “With regard to witnesses in

the tomb robbery investigations, in five cases they invoke the penalty of mutilation and impalement. One witness mentions only impalement.” [10]

All those found guilty of tomb robbing were put to death. The most common form of execution of tomb robbers was that of impalement. Although there is some evidence from a passage the stela from Abydos that forbids trespass, in a sacred part of the necropolis that implies some criminals may have been burnt alive. [11] To be burnt alive had religious implications since it was meant to condemn the criminal into non-existence as there was no body to pass into the Afterlife. Even with these harsh punishments thieves continued to be lured to the tombs for the purpose of fencing goods.

The act of tomb robbery had harsh penalties that would result in the physical and spiritual death of the thief. Despite the best efforts of the Ancient Egyptians to abate criminal activity with added temple defenses, celestial curses and executions, the draw of the vast cache of treasure in tombs was too much of a draw to stop the practice of tomb looting.

Works Cited

Capart, J., A. H. Gardiner, and B. van de Walle. 1936. "New Light on the Ramesside Tomb-Robberies." The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, Vol. 22, No. 2 169-193.

Hussein, Angela. 2012. "Tomb Robbers." Calliope (MAS Ultra - School Edition, (accessed November 30, 2014).) 23 (1): 40 - 41.

Jaroslav, Černý. 1929. "Papyrus Salt 124 (Brit. Mus. 10055)." The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, Vol. 15, No. 3/4 243-258.

Leahy, Anthony. 1984. "Death By Fire in Ancient Egypt." Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient 199-206.

Lorton, David. 1977. "The Treatment of Criminals in Ancient Egypt: Through the New Kingdom." Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient 2-64.

Shaw, Ian. 2000. The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

[1] (Hussein 2012, 40)

[2] (Shaw 2000, 157)

[3] (Capart, Gardiner and van de Walle 1936, 171)

[4] (Jaroslav 1929, 244 -245)

[5] (Capart, Gardiner and van de Walle 1936, 171-174)

[6] (Shaw 2000, 193)

[7] (Hussein 2012, 41)

[8] (Capart, Gardiner and van de Walle 1936, 172)

[9] (Capart, Gardiner and van de Walle 1936, 171)

[10] (Lorton 1977, 34-35)

[11] (Leahy 1984, 199)